One of the better aspects of insomnia is the chance to listen to Radio 4 on the i-player. This week I have been particularly enjoying the Pilgrim series of radio dramas by Sebastian Baczkiewicz. He places English legends in the present day, where the Greyfolk intervene in our Hotblood world in unsettling ways.

One of the better aspects of insomnia is the chance to listen to Radio 4 on the i-player. This week I have been particularly enjoying the Pilgrim series of radio dramas by Sebastian Baczkiewicz. He places English legends in the present day, where the Greyfolk intervene in our Hotblood world in unsettling ways.

It is notable that the contemporary setting makes the eerieness of the traditional tales all the more believable – a kind of corroborative evidence. As a younger reader, I loved much of the work of Alan Garner and Susan Cooper for that sense of it could be happening right here, right now. I still delight in the Narnia Effect of slipping into other worlds, the intersection of the parallel such as Philip Pullman uses. I believe we all like to think we could be the one who notices such things.

What if all the myths and folktales of these islands were true? And what if they were not only true but present now in our world? All the spirits, existing, as they have always existed, in the gaps between tower blocks, in the shadows under bridges, in the corner of our vision…

(from the Pilgrim programme information)

Some writers take another approach: ‘it could have happened’. I think of Pat Walsh and Katherine Langrish with their beautifully depicted historical worlds which also have magic at their core. Some go for an alternative history: Joan Aiken springs to mind and for adults, Susanna Clarke’s ‘Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell’. Here in particular, the sheer detail and interweaving of stories gives an internal validity which I find engaging.

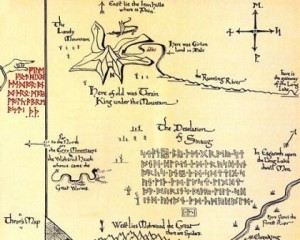

But for sheer consistency of a created world, J. R. R. Tolkien takes every laurel wreath going.

I am almost certain that he once said he wanted to bring back fear into the leafy lanes of England at twilight, to create a truly English legendarium (1). He clearly didn’t intend something twee and Disneyfied: I think he would approve of Pilgim’s dark fantasy tone.

(In fairness to Disney, I have never forgotten Sleeping Beauty’s Evil Queen, or the demon in Fantasia -and I think this is due to the confidence with which they are portrayed – true to their legendary European roots.)

It is the conviction that matters. Read this:

Of all the tales told on these islands, few are as strange as that of William Palmer. Cursed, apparently, on the road to Canterbury in the spring of 1185 for denying the presence of the Other World by the King of the Greyfolk or Faerie himself, and compelled to walk from that day to this between the worlds of magic and man.

Which word sticks out like highlighter on an illuminated manuscript? ‘Apparently.’

For a split second, we step out of the writer’s world and look at it, not gaze round inside with wonder and terror.

Don’t do it.

I am not arguing for the po-faced rigidity of the worst of High Fantasy. A light touch such as in the ‘The Phantom Tollbooth’ or any of the Discworld novels does not distract from the internal consistency of their creations. You go there with the writer as your rather cheery guide.

Indeed, the best writers take the reader by the hand and go side-by-side with them into the terrors and delights of their own universe: think of David Almond. All writers can achieve this credibility – no matter which filter on the spectrum of realistic to speculative fiction they use. The ‘trick’ is to truly be there yourself.

(1) If you can locate the quotation, I would be inordinately grateful to know.

On Tuesday 16th June, I had the pleasure of attending a talk organised by the Sussex Centre for Folklore, Fairy Tales and Fantasy as part of the 2015 Festival of Chichester.

On Tuesday 16th June, I had the pleasure of attending a talk organised by the Sussex Centre for Folklore, Fairy Tales and Fantasy as part of the 2015 Festival of Chichester.