Ever started a book that’s beautifully written and cleverly constructed, perhaps praised by others – and yet failed to get into it? Or gone to see a film with fantastic special effects, witty dialogue and a cool premise – only to find you’re unmoved? I’ve been thinking about what makes the difference, what makes you care…

So this doesn’t ramble on too much, I am sticking largely to books. There may be film references, but I will look through my writer’s gaze hoping to see how I can improve my writing. If you have further thoughts, I would be truly grateful.

I will start with a question:

Does Plot-driven vs Character-driven make a difference?

I think this is a false dichotomy. For a long time, I felt almost ashamed of not knowing my characters inside out before I tackled the first draft. It’s a method that works for some – but not for me ( or Marcus Sedgwick)

“You take people, you put them on a journey, you give them peril, you find out who they really are.”

― Joss Whedon

I find out how my people are by seeing what they do. In all great tales, the action reveals the person and the people shape the events. At any one moment, there are these two dimensions of character and plot, and a third in the reader’s head: what went before. Regardless of genre, in the best stories we want to know how the characters will navigate the events ahead.

“It begins with a character, usually, and once he stands up on his feet and begins to move, all I can do is trot along behind him with a paper and pencil trying to keep up long enough to put down what he says and does.”

― William Faulkner

Where to begin?

It’s a given that we need to care about characters from the first step of our journey with them. So what can attract the reader to walk close by their side and get involved? Something we understand, emotions we share.

Books for children and young people have a fair few ill-treated main characters. From Cinderella to Nathan in ‘HalfBlood’, they suffer neglect from those who should care, injustice or even cruelty. The reader may not have experienced exactly that, but they can imagine being:

- Oliver Twist in the workhouse

- Harry Potter under the stairs

- Matilda in the ghastly Wormwood household

- Jane Eyre in the Red Room

Sometimes the suffering is not deliberate – it comes from tragedy or misfortune. We feel for them and wonder how they will cope:

- Mary Lennox after the cholera strikes ( a brave choice of an initially unlikeable heroine)

- Black Beauty when the stables are sold

- Laurence in ’15 Days without a Head’ coping without his mother

- Sophie in ‘Rooftoppers’ threatened with an orphanage

At other times, it can be a tricky new situation – that unsettling feeling like starting Big School. That uncertainty is something we can all relate to.

- Bilbo finding a wizard and then thirteen dwarves piling into his life

- Tolly in ‘The Children of Green Knowe’ being sent to a great-grandmother he has never met

- Coraline moving to the strange old house and meeting its odd residents

- Tyke finding Danny’s got a stolen tenner (The Turbulent Term of Tyke Tiler)

Is a predicament all it takes?

Simply – no. I could not care less about James Bond no matter how threatened for two reasons:

- He will always succeed.

- It’s all about him.

We are drawn to vulnerable characters who try to do something about the situation. They may have responsibility for others – like Will in ‘The Subtle Knife’. They may try to understand the strangeness of demons (Sally Prue’s ‘Cold Tom’) or the curious ways of Caverna (Neverfell in Frances Hardinge’s ‘A Face Like Glass’). They may take on huge challenges like September in Catherynne M. Valente’s ‘ The Girl who…’ series – but they start off with emotions we can feel, no matter how peculiar the circumstances.

I believe it comes down to how real the characters have become to the writer – and conveying that .

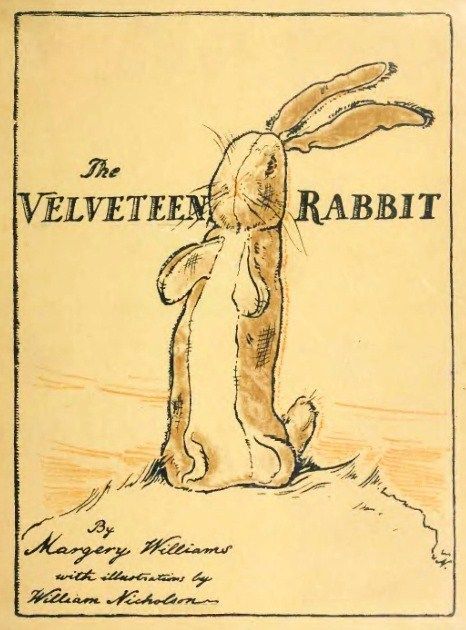

“Real isn’t how you are made,” said the Skin Horse. “It’s a thing that happens to you. When a child loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but REALLY loves you, then you become Real.”

“Does it hurt?” asked the Rabbit.

“Sometimes,” said the Skin Horse, for he was always truthful. “When you are Real you don’t mind being hurt.”

Exactly. I know I sometimes cool on a read where it seems the words are more important than the characters. In those cases, I suppose the writer has just not bothered to hide well enough. Trying to write for myself makes for many initial drafts in order to get to know what the story is trying to tell me and how the characters prefer it to be told. Sounds a bit fey, but that’s the way it works.

Not fey at all, Richard.Thank you for this.