One of the features of a book worth reading is its voice. On panel events at festivals etc you will hear that publishers and agents are always seeking for a work with a distinctive voice.

What does that actually mean? I’m going to explore it in two ways. First, I’ll have a ponder at the voice of the writer – what that might be and where it might come from. Secondly, there’ll be some ideas about the use of voice within a book – together with some tips and hints.

The sad loss of Victoria Wood reminds us of how beloved and effective a distinctive voice can be. Her distinguishing tone was both Northern and humane – at a time when both RP and cleverness seemed to be valued more. So many actors had had to give up their regional voices to succeed: Sir Patrick Stewart from Mirfield in the West Riding of Yorkshire, Sir Ian McKellen from Lancashire and Dame Judi Dench from Heworth near York, for example.

My Dad’s phone voice is pure Alan Bennett – Yorkshire trying to be posh.

Happily writers like Victoria Wood and Alan Bennett held onto theirs. It’s part of who they are – in the same way you always know a Pam Ayres when you hear it. I am a little biased in favour of the North – but the point I’m making is that wherever you come from informs your physical voice and the way you write.

Joanne Harris “Not posh – just half French”

The other aspect that shapes the voice across an author’s written work is their personality – or at least the side we get to see on the page. I suspect at least half of Victoria Wood’s appeal was her clear interest in people and kindly humour about them. If she drew cartoons they’d be more Thomas Rowlandson than Gerald Scarfe.

Discomforts of an Epicure; self-portrait by Thomas Rowlandson Self-deprecation is endearing.

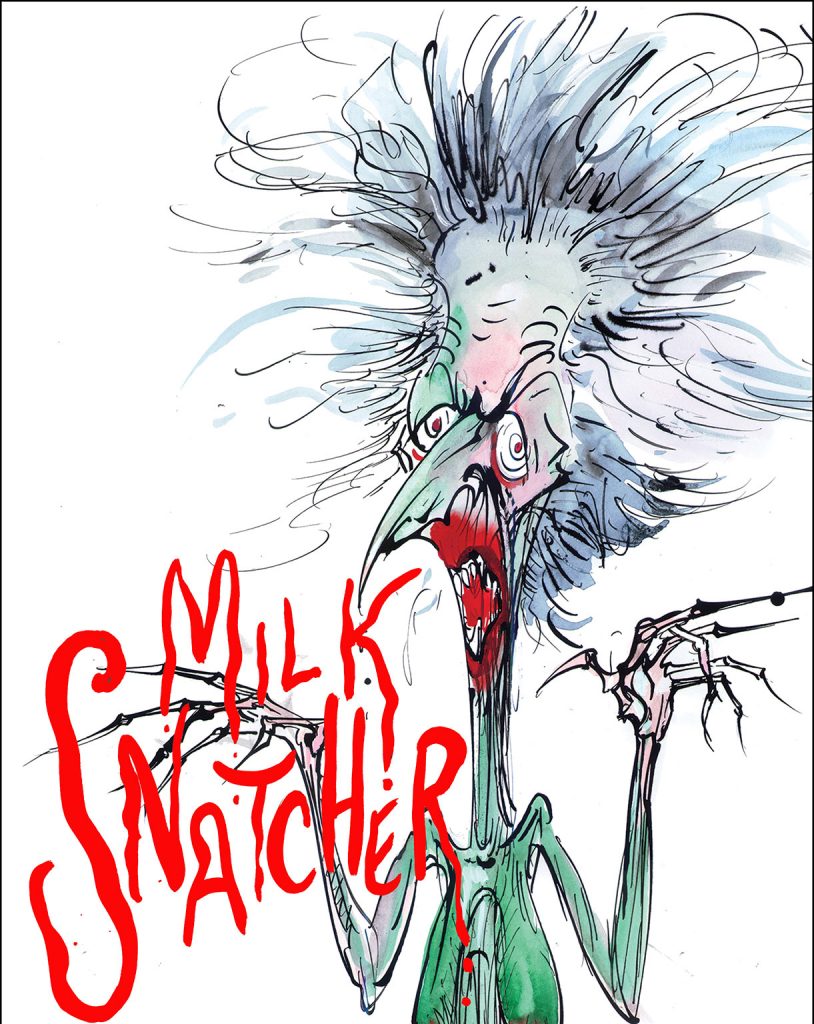

Gerald Scarfe, Thatcher – Milk Snatcher © The artist Vicious, angry, stylish.

That personal aspect of voice appears across all work from a distinctive artist – and deepens over time. But what about voice within a piece?

This too subdivides – there’s the tone of a whole novel, and the voices belonging to the characters. Where there’s more than one point-of-view character, the difference between them becomes essential. Imagine how tiresome Joseph O’Connor’s The Star of the Sea would be if all four main narrators sounded the same? As writers, we can’t rely on marvellous actresses like Juliet Stevenson to make them clear: we have to do it in the reader’s mind.

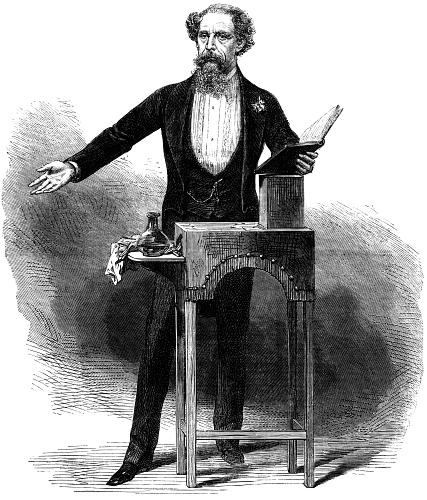

Dickens was famed for reading his own work well: ‘He do the police in different voices.’

How?

- word choices – a different box for each character to pick their usual diction from

- syntax / grammar / the way they phrase sentences or fragments of speech

‘I love pies, me.’

- word order

‘Give it me here.’

- length and completeness of sentences

- whether they use clauses for extra information or for modifying – or not

Why? (Other than to tell them apart)

To convey what influences them:

- class

- education

- gender

- age

- region – dialect, idiom

- culture and family – patois

- location – urban, suburban, rural

- friendship groups – slang / shared vocabulary

- work +/or passions – what combination of scientific, literal, artistic, metaphorical, jargon-loving, lyrical etc?

- character traits – spare with words through caution or shyness? Voluble because of enthusiasm – or nerves? Formal or cheeky?

Practical tips

- establish the new voice immediately when using a different point of view

- make a style book as you go along to reinforce the differences – keep revising it

- edit one voice at a time

- read aloud

As for the voice of a given book, I’m not sure about explaining that. Do you have any thoughts? Please share in the comments below – I always read them and answer back.