First part of a fairy story for writers.

A blind girl took a notion to become a seamstress. She had always loved the feel of clothes – in net skirts she could be a dancer, light as a fuchsia flower; in vast satins, become an Empress; or in soft, washed cottons, a dreamer of discoveries.

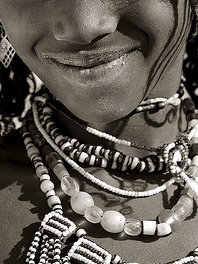

Oh and the feel of them! To rub the smoothness of ribbon on her top lip. To slip the inside of her wrist past the tickle of feather trims. To tap the patterns of sequins and beads with her fingertips.

Dressmaking she knew was more than these lovelies thrown together. Had her palms not patted the outlines of sleeves and bodices, then clasped at waists and swept down full, swirling skirts? Therefore she would seek out someone to learn from, a Queen of the Needle to train her hands.

Now the blind girl found one such instructress. She learned much from the Bearer of the Golden Thimble, as did the others in her Court. The redingotes and mantuas, farthingales and houppelandes of all places and all times were spread before them as treasures to imitate and learn from. It was a tiring sort of bliss.

The day came when our girl made her first full dress. The Sighted Ones came and said that it was good.

Yet this was not enough.

‘I want to be as other seamstresses,’ she said.

‘My skin has felt their wondrous gowns upon it; has touched the furred luxury of a patrician’s robes; has worn the velvet of the soothsayer and the mail of a knight.

I have seen how their seams fit, the gores and the box pleats, the hems and the gussets. And I know that their clothes are beloved.

If I make a dress of my own devising, won’t somebody buy it? And then I shall know I have done well.’

She set to work.

She asked advice and many were the answers. This year muslin alone was being bought – no, seersucker was quite the go. Lace had to be the very thing – nay, but damask could only please.

She made her dress as she felt right; made it such as would fit herself.

Friends told her it was a lovely thing.

‘Then I shall take it to market,’ she said.

Now it so happened, she had learned the ways of the Sighted and could pass for one at first and maybe second glance. It was not a strangeness for her to be there, it seemed to others, though it caused a tumult in her chest. She stood in the Place of New Garments and held out her dress.

‘Who will buy?’ she called.

Feet came. Her heart rose in a fountain, all domes and bubbles and joy.Other fingers made her dress sway, touched its threads and gathers. This was her break in the clouds, when the sun would kiss her cheek.

‘Perhaps another day,’ one said.

‘Let me try – alas, but it does not fit,’ said another.

‘Not quite what I desire,’ said a third.

She heard the pity in their mouths roll like cherry stones, caught the tinkle of earrings as they shook their heads. At length, the evening came and no-one had bought, although many had given counsel.

She went home. She unpicked and sewed all through the night. The lack of candles was no obstacle to her. Hours filled with the tingle of coffee she took to make it all anew.

The next market day came. She stood beside her dress on its wire-busted cage and called for buyers. Feet came and went. She recognised the passing scents of her companions from the Court of the Golden Thimble. They tossed encouraging remarks to her then passed into the Great Bazaar. Calls of acclamation greeted them and the brass gates clanged shut.

Still no-one bought her dress. All through the hot afternoon, above the air layered with sweat and donkeys and oranges, she heard the clamour of the souks. One day she would surely trade there, hear delight in the voice of a buyer, do what her hands had folded in prayer for.

The cool of evening fell on her neck like a rinsed veil. She took down her dress and walked home alone. The wire stand weighed heavy under her arm.

Market Day followed Market Day like camels in a train. Traders to the left of her and to the right of her sold their djellabahs and left. She smiled for their success and waited for her turn.

It did not come.

Then one night, in the chill of the sleeping city, alone, she leaned against the doors of the Great Bazaar. The brass dragged the warmth of her skin into its engraved geometry. She let the dress slump over her arm, a dead thing of pulled threads and puckered selvedges. A light wind raised its tattered hem then let it fall.

‘I can do no more,’ she said to the whirls of sand dancing around her feet. ‘My notion was a foolish one. I will go back to the village and wash fruit for my living.’

Then she walked towards the heat of the night-watchman’s brazier, where beggars belched cheap palm wine and street dogs scratched. The crackle of burning sticks would give her a place to aim – she had to stop and listen. Her cheeks grew taut.

‘May this warm a poor man’s palms,’ she said, forgetting that she spoke aloud. She balled the cloth and tossed it to the flames.

But the dress never reached the fire. A hand caught it.

to be continued.

Woo hoo! That is beautiful. Can’t wait to find out what happens next!

That’s kind of you, Candy. I think you are my most loyal reader. 🙂

Lovely story. It’s just like writing. Write us a happy ending and it might come true for us all.

Thank you Debs – and good to read your comments here for the first time.

Love the sewing analogy, Philippa. I’m hooked – next week for part 2?

Definitely – I do hope I get the terminology right, O Mistress of the Machine that Sews.

Brilliant! Beautifully crafted—love the sound of all those sewing terms. Great writing analogy.

Oooh you have made me happy, Dave.

Pingback: Ten-Minute Blog Break – 18th February | Words & Pictures