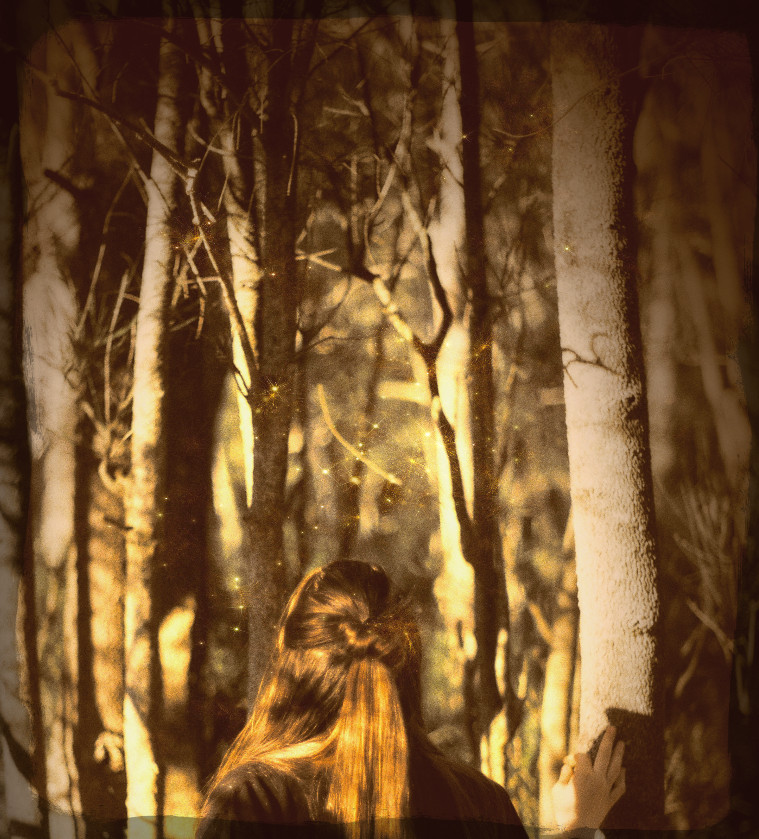

This is a tale told in twigs dropped by crows along a wildwood path . . .

The Pilgrim told this tale on a long evening in the time of pestilence:

The villagers began with a moment of silence. It were a serious matter, not to be taken lightly. Nine beats of a crow’s wing they waited, then took a great inward breath of pine and leafmould.

The wood watched, and all its indwellers; the named and those who are only hinted at. It dint do to rouse them by careless words, so the villagers worked in quiet.

Speech dared only come out to save fingers from blades, to protect heads from low boughs or to warn of passing loads. Still, at every gathering of brushwood, at every stroke that bit into a trunk, thanks were given.

This load needed to last. It needed to burn well throughout the season of long nights. Courting ill will from the Grey Folk were not the custom – nor were it wise.

Mirabelle, too small and milk-fed to do more than pick up dropling twigs, saw the first of the Grey Folk. Her wondering, open-gobbed look followed its scampering gait. Too young to know better, she pointed and tugged on the leather brat her father wore round his waist.

He lapped a hand worn and speckled wi sawdust over her grin. ‘Hush lass.’ He leaned down and whispered in her curls so fierce they danced. ‘No gawkin at the fairishes. Curtsey and turn round three times sunwise and happen it’ll come right.’

He span his daughter round. His face crumpled with worriting.Had her manners been enough to ward off disaster? They’d surely see o’er winter. Grey Folk had many ways of vengeance; suffocating vapours from banked fires, exploding logs burning down houses, the wrong mushrooms on the drying strings leading to small graves.

He doffed his cap to the departed boggart or whatever it were. Who knew what gawked from the bramble-caged shadows?

Mirabelle did not forget what she saw. Every autumn she peered into the woods, and marvelled at the colours. Every time she hoped to see summat through the leaf fall, summat that would show it were true.

Winters came and went without their ling thatch roof catching fire, nor any more blight in their garden than were natural. She grew and proved useful. Her father’s careful watch over her lessened.

Tasks he had aplenty in the shortening days of each autumn. Willingly she did those close to the the shadowed edgelands between their land and the home of the Grey Folk. Glance after glance she sent through the wind-stripped trees.

Happen she heard singing and happen she glimpsed misty shapes traipsing among creaking branches – but happen it were wishful thinking. Foraging and pickling, weeding and harvesting, drying and salting left time enough for dreaming.

One day, as autumn dropped her dagged and coloured cloak at winter’s brisk demand, Mirabelle found herself alone and choreless. She slipped away to the tufted edge of the greensward where toadstools marked the border and stepped into their world.

She wandered and tree roots rose to tilt her feet into tripping. Hanging brambles clawed at her cheek. Did the Grey Folk want her to go back? Nay, that were the way of the woods – full of snares and catches.

She stumbled on, half-hearing old songs, sniffing at impossible summer scents, fondling crinkled bark with pleasure. Words of joy and thanks fell out of her lips. Who am I talking to? she asked herself. For all her thoughts, she could not shake off the need for speech.

A path strewn with leaves of scarlet and gold, vermilion and saffron led her to a delph. There in the mothy quiet, she spun round three times, arms out wide, face lifted to a cool blue sky. Only then did the silvery voices welcome her back home.

Mazy with gladness, she leant agin a smooth elm and undid a boot. She threw it away like a shackle. Then she pulled off her coarse woollen stocking and let it drop like so much snakeskin. She swapped legs. When both were bare, she plunged her feet through crackling leaves to the moss beneath.

She were forced to dance and run and sing. Her bones were light as breeze-blown stalks. After a wild session of chorusing and frolicking, she stopped still. Those boots weren’t a fit offering to leave in these woods.

It took little time to find them – dark blotches that reeked of cattle dung and the hide of dead creatures. The nasty metal lace holes glittered, rows of threaded eyes acccusing her. She latched hold of the laces, avoiding the cold iron circles, and flung the boots over her head. She skipped towards the edge of the woods, picking up needful things as she went.

At the last copse before the hovel, she halted. She gave thanks to Mother Birch for a square of her skin, to Maister Magpie for one of his feathers, and to the toadstool tribe for a few drops of their dark blood.

She sat cross-legged in the cupped palms of a patch of sunlight and wrote this note:

To the ones who told me they were my parents,

When you read this, no blaming the Grey Folk or the Fairishes or whatever you call my people. They did not take me – I came by mi sen. I came since these are my woods. I came since I am free here. I came since I am not your daugher but one of theirs.

I’ll not forget the kindnesses given – the woods will never be a danger to thee – but I mun return where I belong,

Thi once-upon-a-time child of bark and dreams

Mirabelle

She pinned the note to the hovel door with a blackthorn spine. Her feet left no mark on the path for all her tripping along, and though her singing were heard in among the hollins, she were never seen again.

****************************************************************************************************Original image by Caitlin Venerussi on Unsplash , adapted by K. M. Lockwood

Such beautiful words and a lovely photo. It is magical xx

How kind of you, Susan. It’s a joy to know you’re reading the Tales from the Garret.

Wonderful and full of magic! A real delight.

Thank you so much for taking the time to tell me. Much appreciated, Pat.