Geek Sphinx by Mage Cat

Last week I considered metamorphosis – prompted by listening to Dame Marina Warner at The Sussex Centre for Folklore, Fairytale and Fantasy. Whilst I was pondering unnerving transformations, images of many strange mythical hybrid creatures came to mind (some prompted by this month’s Mslexia.) What is their attraction – and what does it matter to modern storytelling?I have tried to herd these monstrous or mythological beings into groups. It’s not easy shepherding the uncanny. First off, those with clearly human aspects. A few examples who are half human, half beast:

- centaurs

- mermaids

- the Minotaur

- sirens

- Melusine

Traditionally, each of these has its dangers: centaurs can turn wild in a moment, mermaids and sirens lure sailors on to rocks with their singing, and the bull-headed Minotaur eats anyone who ventures in the labyrinth on Crete. And yet most are attractive in some way.

Another variation on Melusine

Melusine is a beautiful queen, but a serpent from the waist down in water. When spied upon in her bath by her husband against his promise, she turns into a dragon and flees. Despite the apparent horror of this, many noble families once claimed to be descended from her.

Next come what I describe as marvellous mixtures – made from a selection of animal features. Here are a few:

- wyvern – two legs like a bird of prey, bat wings and the tail of dragon

- gryphon or griffin – body and legs of a lion, head and wings of an eagle

- manticore – red lion’s body, a man-like face with sharp teeth and sometimes tusks, and the tail of a scorpion

- cockatrice or basilisk – a cockerel with the tail of a snake able to kill by a glance, or hissing

- hippocampus – part horse, part fish, sometimes with wings and webbed feet

Arthur Charles Fox-Davies [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons – in heraldry, this is a sea horse.

Last in my grouping – the deities. Ancient Egypt in particular had a wondrous pantheon of gods and goddesses with animal aspects. Sometimes they would assume a complete animal form, but also often appeared as part human, part animal. Being able to change at will makes them distinct from the first set – and links with shape-shifting.

- Sekhmet – lioness deity of war and love

- Hathor – cow goddess of joy and fertility, guider of souls to the afterlife

- Thoth – ibis, sometimes a baboon – god of wisdom and magic

- Bastet – cat goddess of family and music

- Anubis – jackal god of death, embalming and justice

Once at the British Museum, I had the good fortune to talk to a curator ( or is it curatrix?). She agreed with my theory – which I may have come across but couldn’t recall where – that the Ancient Egyptians didn’t actually believe that Sobek had the head of a crocodile. They knew perfectly well Pharaohs were not ten or twenty times bigger than other humans but chose to show them that way to convey their power and status. The same with the deities: the animal appearance embodies their personality and powers.

![By Hedwig Storch (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://kmlockwood.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Kom_Ombo_Sobek_0342-683x1024.jpg)

Sobek by Hedwig Storch (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Thus even in apparently realistic stories, a dreadful protagonist will follow this pattern. A true monster has something in them we find attractive or can identify with. That is what we find so compelling and distressing – the part we recognise is inseparable from the whole being.

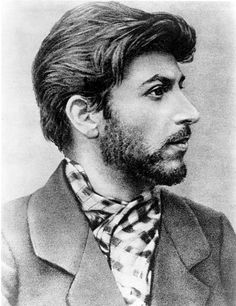

Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili- 23 year old Joseph Stalin

That’s fascinating. So Darth Vader’s allure as a monster is the fact that he fathered someone pure like Luke Skywalker. Creating a character that both draws and repels the reader takes admirable skill.

Thanks, Candy. On further thought, the most effective villains for me are those who just *might* reform. They have a chink of light in them – and this crack or weakness my be how our hero/ine defeats them.

I so appreciate the comments you put.