My title this week comes from an article in the Guardian about the artist Eric Ravilious, famous for his watercolours of the Sourh Downs. I went to see an exhibition of his more commercial works on Wednesday 16th October at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester. (It’s on until 8th December, well worth a look – and that section of the gallery is free.)

The night before I’d been to see Neil Gaiman read Fortunately the Milk in London. he was asked by tweet where he gets his creative energy from. I’m paraphrasing so it’s not exact but his response was that he enjoys creating.

I should have expected that. It comes over in his exuberance and his mad hair.

Now for the connection with a somewhat obscure artist of the 1930s, whose work is instantly recognisable, distinct and for me a source of delight.

In the exhibition, you can see how Eric Ravilious made little everyday things like letter heads cheerful. His playfulness comes through in the artwork.

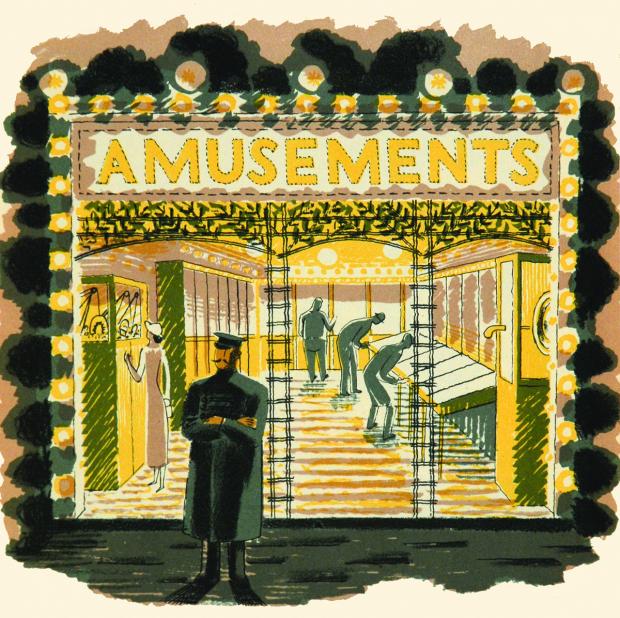

And it isn’t just appealing subjects like arcades.

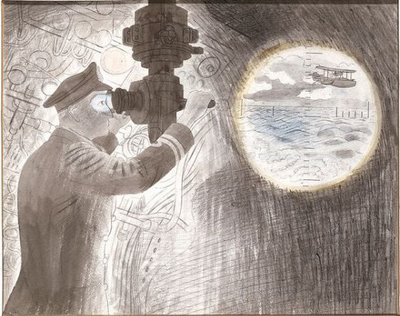

He gives even life in submarines a certain jauntiness. Some of that stems perhaps from his personality – see The Guardian article – yet I suspect something more than just lightness of touch.

There’s more to why he engages contemporary viewers. A sense of ‘interestedness’ in his work. That he took time to observe and delight in the particular. To see specific details in almost anything that set it apart.

An example might make what I mean clearer.

He produced the delightful illustrations in 1938 for ‘High Street’ – a book for children about shops.(A plea to Mainstone Press who publish lovely books including collections of Ravilious’s work – please could they redo this one in a format a poor writer can afford!)

They are in some ways generic – typical of all shop fronts. I would guess a woman from Kyoto could look at them and see something recognisable. Yet they each have exact and carefully rendered differences apart from the obvious names and articles for sale. He hasn’t done a visual copy-and-paste. He’s looked for interesting bits to put in.

I would imagine they come from lots of sketchbooks – and that the finished works are a mixture rather than an exact reproduction of any one real scene.

I see that as a metaphor for good, enjoyable writing. We look for the specific and the interesting to give life to our work. We get a buzz from observing and then assembling all these snippets and sketches in pleasing forms. Same as any creator, I suppose.

And I think of the era in which he was creating. Of how he was lost at sea near Iceland in September 1942. He wasn’t making superficially jolly work in easy circumstances.

A Ravilious woodcut showing the Long Man of Wilmington – and Taurus.

That’s what the best of creativity does: it finds and produces beauty wherever we are. It brings hope.That has to be a source of joy.