More in the story begun last week.

The blind seamstress drifted away along the usual streets with the smell of charcoal behind and hammering of brass ahead to guide her. Her head drooped like a parched lily bloom. Her sandals pattered on palm fronds and sank in silence on carpets left outside coffee houses.

Two other feet did the same. Leather soles touched down behind her with a tread too light to raise the dust. A woman followed her, of that she was certain.

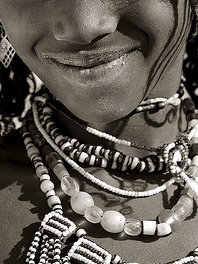

She let the night air bring her clues. This woman wore Attar of Roses and bangles tinkled on her wrists. Coins tapped against each other on her headscarf, and ankle chains jingled with the laughter of riches.

If she tilted her head, the swish of fine silks swept in, no noisier than the river whispered.

And what did it whisper to her? That she should settle for a life of hefting watermelons and slicing them for passers-by. That the scent of tangerines and lemon rind would be the perfume of forgetting. That contentment would be best found in letting some dreams drift away on the stream.

She went on towards the sweet damp of the riverside and her little home.

‘Stay,’ a voice called. A voice of refinement and calm. A voice used to its owner’s worth.

The blind seamstress clasped the friendly ragged trunk of a palm. Something so steady must give her courage.

That a Sighted One should speak to her on the mud banks!

‘Stay – and talk to me of this dress,’ the Rose Lady said.

The light breath of the river ruffled something in the Rose Lady’s arms. Something made of cotton and thread and dreams.

‘Come – sit with me and tell me of the hope still scorching a corner of your heart.’

And they sat and drank coffee in the reed-hushed night. And when the seamstress had spoken of the desires rooted deep in the warm earth of her heart, and had not been mocked, she dared ask the Rose Lady’s counsel.

‘I cannot weaken the truth – for what good can a medicine do if too much water be added into it? You have much still to learn if you would have your garments bought.’

She put a hem in the hand of the seamstress.

‘Feel how this is too uneven – like the back of a crocodile, it goes up and down.’

‘But I wanted a wave – like the riding of a dhow beside a jetty.’

‘That is not what I see.’

‘What can I do when I am not sighted like others? How can I ever get any better?’

Despair gushed up inside the blind seamstress, as viscous and stinking as asphalt. It dragged wretchedness and every memory of failing with it like grit. The seamstress wept.

The Rose Lady stopped her tears with sweetmeats and dates. She made the fingertips of the seamstress feel the faults and knots, bunched cloth and puckered linings. The Rose Lady made her smell the dyes – nose-itching turmeric root for golden yellows, the pea stench of indigo blue, and the gingery tickle of red madder.

‘It is like making pilaff – too many tastes at once and your tongue is confused. So it is with colour. Too little and the gown is dull, too much and only a spangled acrobat could wear it.’

‘Teach me more – tell me what to do.’

The Rose Lady passed over a sugar-dusted cube of lakhoum but said nothing. The seamstress let it dissolve on her tongue but all its sweetness could not wash away the gall of fear.

It came out in a bitter whisper.

‘The others are better than me.’

The Rose Lady’s gold tinkled and did not agree.

‘Ah, but they have not your ways with the needle,’ she said.

‘They do not choose as you do – they have not fondled cotton on the bolt nor traced the patterns of damask with your fingers. You hold each dream within your palms as the potter does the clay. It turns and has a thousand-and-one sides to it and all bear the imprint of your skin.’

She sipped her coffee. Swamp-hens called in the reeds. The seamstress considered.

Then she took off her headscarf with its scant trim of coins. She laid it across her open palms and knelt with her arms held out.

‘Take these and tell me what I should do, I beg of you.’

The Rose Lady made her fingers close around the thin linen and the single line of discs.

‘I would not hear of it, dear Child of Promise. I can only tell you what is wrong – I cannot right it for you.’

She placed her hand over the mouth of the seamstress before she could cry out.

‘I would not even if I could – I do not seek to deny you.’

A sigh disturbed the bared curls of the seamstress. The Rose Lady took her hand away from her lips.

‘Whatever you make from your own faults and fumblings, that is yours – it belongs to you. And that makes it precious. If I say ‘do this’ and ‘do that’, it will be as plaster for marble, or painted wood for bronze – all semblance and no truth.’

The voice of the seamstress brightened. The richness of ‘promise’ and ‘precious’ fed her hopes.

‘Please help me make the best dress I can.’

The Rose Lady spoke and there was a chuckle in the depths of her throat. It sat there, smoky and subtle as the charred skin on the aubergine flavours babaganoush.

‘It will not be one dress, sweet child – but many. Your fingers will bleed and your sinews will ache, and Unease will always stalk you – yet will you follow my path?’

‘Whilst my heart beats I will try.’

What would you add to my list?

What would you add to my list?