This post owes its parentage to Vanessa Harbour on ‘The importance of reading as a writer’ and Maureen Lynas’s writing about an approach to structure. I thank them both for getting me thinking about what I read and how it affects my writing.

One notable feature of the MA at West Dean was the challenge of reading in new genres. Without that I would never have discovered the emotional intensity of ‘A Quiet Belief in Angels’ by R. J. Ellory or to be honest ,the complex and satisfying structures used by Agatha Christie & Ngaio Marsh. I didn’t ‘do’ crime fiction before. It’s taught me to be an even wider ranging reader.

Now I enjoy being sent books by Vivienne Da Costa for Serendipity Reviews. There are joys like the sheer delight of seeing a much-liked author Chris Priestley come into his own – really using his deep knowledge to create ‘Mister Creecher’. Or the pleasure of reviewing a colleague’s debut novel like ‘Slated’ by Teri Terry.

I am sent different age-ranges and genres – this helps me to see what I admire, and also what I don’t want to write.

Greg Mosse insists students understand that it’s not what we like in a Reading-Group-glass-of-wine-and-nibbles way that matters, but what works. To my family’s annoyance during the MA year I couldn’t watch anything without taking it apart to see the gears and cogs. I keep quiet now – but I’m still anatomising in my head.

And yet…

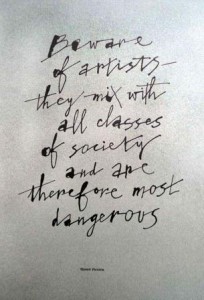

It’s not just that, however useful. It’s about inspiration. The things that make me want to write.

This will sound cringeworthy but it is true: I want to pay it forward.

I want to take readers to new worlds.

I loved Narnia and Earthsea and Pern and Middle Earth ( yes I know -it’s our world millenia ago). How wonderful to transport other people somewhere special.

I want to speak with my own voice.

I can hear writers like David Almond and Robert Westall, and Leon Garfield and Joan Aiken. They taught me I can be myself, Northern vowels and all. That you can use language to give flavour and identity. I want to share that.

I want to revel in reworked tradition.

I think of Alan Garner, George Mackay Brown Lloyd Alexander, Susan Cooper and nowadays Katherine Langrish, Jackie Morris and Pat Walsh. They develop shared folklore, myth and legend and keep it alive. It’s too good not to pass on.

I want to express my delight in transformation.

Books move me far more than cinema or TV, they always have done. I can never forget the change in Mary Lennox in ‘The Secret Garden’, or Eustace Clarence Scrubb in ‘The Voyage of the Dawn Treader’. And I’m still a soppy date about Scrooge & Silas Marner. Who wouldn’t want to show what people can become?

So, in short, I think you have to read and read and read to be even a halfway decent writer. Or at least I do.

How about you?