David Almond’s handshake was warm and strong. He was welcoming and unpretentious though the delegates were quiet and perhaps, like me, thought – that’s David Almond, that is – and I’m here in the same room. Me.

Despite all that hero-worship, he encouraged us to offer own work written oh-so-quickly there and then. He gave off appreciation and candour – even to Mrs Gobby here. In the spirit of that openness, this post will be about those elements of the master-class that really touched me. They are interspersed with some of my images of Newcastle to give you pondering time. The quotations are David’s, the rest is my understanding of what he said.

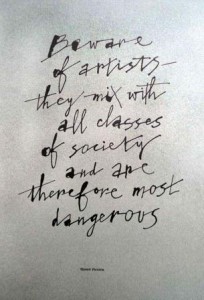

Protect yourself as a writer.

Wherever you are along the writer’s way, you need things to sustain you. You will feel ‘stupid and insignificant and rejected’. There will be moments of bitterness and frustration. David said ‘create your own mythology’ of how you came to be a writer as something to draw on.

Honour your own work.

Every day find that piece which is you – identify what’s authentic. Where have you connected with the story and transcended the obvious ? What resonates? Get that stuff out and value it – it might be scary but it is truly yours.

Indulge in the process.

Being playful allows you to be all sorts of writers. You never know what sort of writer you are until you become that kind – it’s a sort of acting. When you think about it , as he said, ‘My Name is Mina‘ by David Almond is such a pretence. Playing lets you be ‘alert and relaxed’ without the brain too engaged – the ideal state for writing. He likes to scribble, to jot, to rough things out by hand – it leads to messy notebooks and a sense of freedom. Speed can help too.

Find unexpected opportunities in yourself.

‘Stop fighting yourself – let who you are out’. Such an inspiring thought – that it’s our imperfection that generates creativity. ‘Sometimes the things you draw on you might not want to’ he acknowledged – but he rejected the concept of challenging difficult emotions and experiences.

Writing well comes from every art of you.

It’s not about confronting –

it’s about allowing.

There was more about about turning ‘the mess in your head into straight lines on the paper’ but I want to finish with what seems to me the fundamental notion of writers I admire:

To write a book is an act of great hope.

My hope is that one day a book will come to me as Skellig did – ‘full of energy and grace’. Meanwhile, I will take advice that I have had from many different sources ( David Almond, Greg Mosse, Celia Rees, Linda Newbery…) – write some more.